會說話的兒童文學雙月刊

(2020-21, Vol 2)

Now this is the Law of the Jungle — as old and as true as the sky;

And the Wolf that shall keep it may prosper, but the Wolf that shall break it must die.

In the jungle, the Law runs forward and back —

For the strength of the Pack is the Wolf, and the strength of the Wolf is the Pack.

The Jackal may follow the Tiger, but, cub, when your whiskers are grown,

Remember the Wolf is a Hunter — go forth and get food of your own.

Keep peace with the Lords of the Jungle — the Tiger, the Panther, and Bear.

Don't trouble Hathi the Silent, and don't mock the Boar in his lair.

When Pack meets with Pack in the Jungle, and neither will go from the trail,

Lie down till the leaders have spoken — so fair words shall prevail.

Now these are the Laws of the Jungle, and many and mighty are they;

But the head and the hoof of the Law and the haunch and the hump is — Obey!

Hamlet: Let me ask you this, my friends. What have you done to deserve to be sent to prison?

Guildenstren: Prison, my lord?

Hamlet: Denmark's a prison.

Rosencrantz: If Denmark's a prison, is the world also a prison?

Hamlet: Yes, a huge one. There are many confines, wards, and dungeons in this world. You can call many places a prison. Denmark is one of the worst prisons.

Rosencrantz: I'm afraid we don't think so, my lord.

Hamlet: Then, I guess Denmark isn't a prison to you. After all, nothing is either good or bad by itself. Things are only good because we think they're good. It's the same for anything bad. To me, Denmark is a prison because I think it is.

Rosencrantz: Denmark is only a prison because of your ambition. It is too small for your mind.

Hamlet: Oh God, I could be bounded in a nutshell and still think I am a king of infinite space, if I didn't have all these bad dreams.

Guildenstren: Dreams are a sign of ambition, since ambition is nothing more than the shadow of a dream.

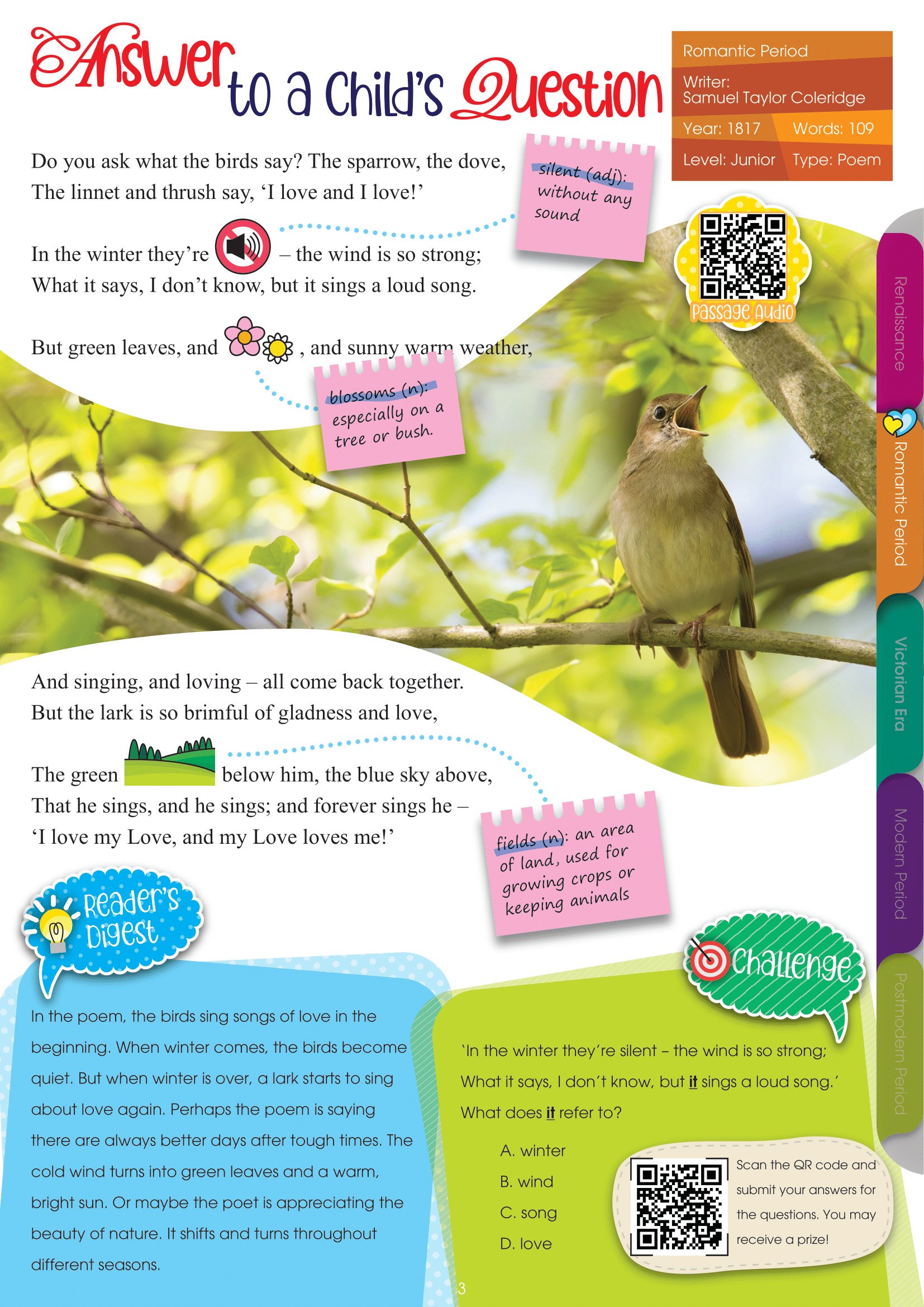

Do you ask what the birds say? The sparrow, the dove,

The linnet and thrush say, 'I love and I love!'

In the winter they're silent – the wind is so strong;

What it says, I don't know, but it sings a loud song.

But green leaves, and blossoms, and sunny warm weather,

And singing, and loving – all come back together.

But the lark is so brimful of gladness and love,

The green fields below him, the blue sky above,

That he sings, and he sings; and forever sings he –

'I love my Love, and my Love loves me!'

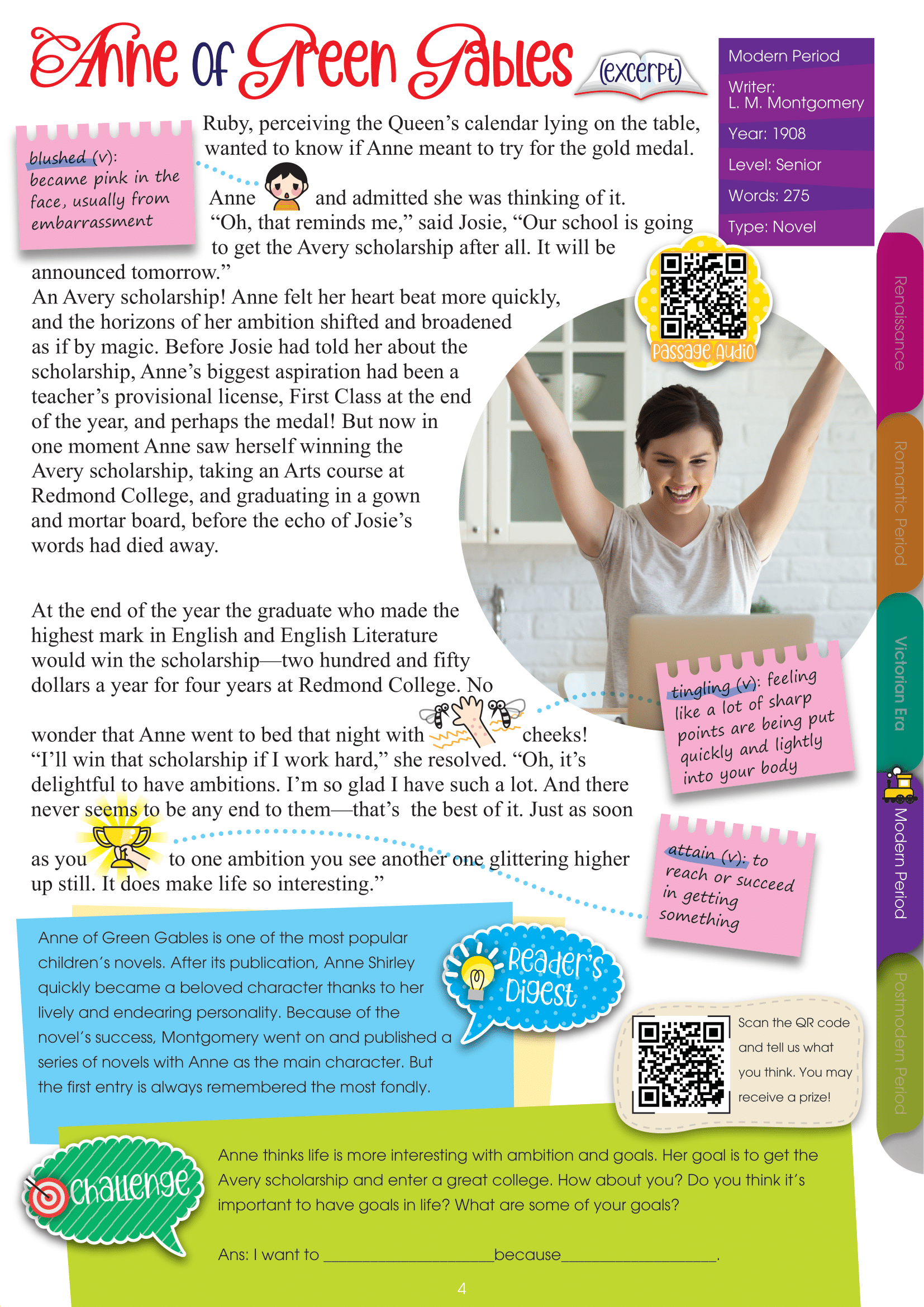

Ruby, perceiving the Queen's calendar lying on the table, wanted to know if Anne meant to try for the gold medal.

Anne blushed and admitted she was thinking of it.

“Oh, that reminds me,” said Josie, “Our school is going to get the Avery scholarship after all. It will be announced tomorrow.”

An Avery scholarship! Anne felt her heart beat more quickly, and the horizons of her ambition shifted and broadened as if by magic. Before Josie had told her about the scholarship, Anne's biggest aspiration had been a teacher's provisional license, First Class at the end of the year, and perhaps the medal! But now in one moment Anne saw herself winning the Avery scholarship, taking an Arts course at Redmond College, and graduating in a gown and mortar board, before the echo of Josie's words had died away.

At the end of the year the graduate who made the highest mark in English and English Literature would win the scholarship—two hundred and fifty dollars a year for four years at Redmond College. No wonder that Anne went to bed that night with tingling cheeks!

“I'll win that scholarship if I work hard,” she resolved. “Oh, it's delightful to have ambitions. I'm so glad I have such a lot. And there never seems to be any end to them—that's the best of it. Just as soon as you attain to one ambition you see another one glittering higher up still. It does make life so interesting.”

“Please, God,” she whispered into the palm of her hand. “Please make me disappear.” She squeezed her eyes shut. Little parts of her body faded away. Now slowly, now with a rush. Slowly again. Her fingers went, one by one; then her arms disappeared all the way to the elbow. Her feet now. Yes, that was good. The legs all at once. Almost done, almost. Only her tight, tight eyes were left. They were always left. Try as she might, she could never get her eyes to disappear.

It had occurred to Pecola some time ago that if her eyes, those eyes that held the pictures, and knew the sights—if those eyes of hers were different, that is to say, beautiful, she herself would be different.

Her teeth were good, and at least her nose was not big and flat like some of those who were thought so cute. If she looked different, beautiful, maybe Cholly would be different, and Mrs. Breedlove too. Maybe they'd say, “Why, look at pretty-eyed Pecola. We mustn't do bad things in front of those pretty eyes.”

Each night, without fail, she prayed for blue eyes. Fervently, for a year she had prayed.

Although somewhat discouraged, she was not without hope. To have something as wonderful as that happen would take a long, long time. Thrown, in this way, into the binding conviction that only a miracle could relieve her, she would never know her beauty. She would see only what there was to see: the eyes of other people.